These are words and saying that are from different cultures in which I have discoved and wrote down because I appreciated what they stood for. I wanted to share these sayings with whoever stumbles upon this page to reflect and appreciate what they offer in perspective and heart. Enjoy!

Ichi-go ichi-e (一期一会)

Ichi-go ichi-e is a Japanese four-character idiom meaning “one time, one meeting.” It emphasizes that every encounter is a unique, once-in-a-lifetime experience that can never be repeated in exactly the same way. Rooted in Zen Buddhism and the Japanese tea ceremony, the phrase encourages us to be fully present and to treasure each moment, whether with people or in everyday life, because circumstances, feelings, and time itself are always changing.

Ubuntu

“I am because we are.”

Ubuntu is a profound Southern African philosophy emphasizing that our humanity and identity are deeply interconnected. A person is a person through other people. It highlights community, compassion, and shared humanity over individualism, reminding us that individual well-being depends on the well-being of the collective. Ubuntu is a call for mutual respect, kindness, and the understanding that one person’s flourishing is tied to the flourishing of all.

Wabi-sabi

Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic and worldview centered on finding beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. It embraces the natural cycle of growth, decay, and weathering as signs of life and character rather than flaws. Drawing inspiration from Buddhist teachings on transience, wabi-sabi encourages simplicity, quietness, and harmony with nature, offering an alternative to Western ideals of perfection by honoring age, wear, and asymmetry in objects, landscapes, and life itself.

Tikkun Olam (תיקון עולם)

Tikkun olam is a Hebrew phrase meaning “repairing the world” or “healing the world.” It refers to the idea that people have a moral responsibility to make the world more just, compassionate, and whole through their actions. Tikkun olam suggests doing something with the world that not only fixes what is broken, but also improves upon it—helping prepare it for the state it is meant to become.

The world is imperfect—and you are not here by accident.

Your actions matter.

Repair happens piece by piece, person by person.

Hao La (好啦 / 好了)

Hao la is a commonly used Mandarin Chinese expression that can be translated as “it’s okay,” “all is well,” or “it’s getting better.” More than a phrase, hao la often carries a sense of reassurance and calm—an acknowledgment that things may be difficult now, but they are settling, softening, and moving toward balance.

Eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία)

Aristotle, an influential philosopher in virtue ethics, claimed in Nicomachean Ethics that the goal of human life is eudaimonia, often translated as living well or human flourishing. He argued that eudaimonia is achieved through consistently practicing virtue over time. Acting virtuously meant choosing the mean – the balanced middle – between vices of excess and deficiency. For example, courage lies between cowardice (deficiency) and recklessness (excess).

Central to Aristotle’s ethics is the idea that moral virtues such as courage, honesty, and wisdom are developed through habit and education. By repeatedly choosing virtuous actions with intention, individuals shape their character. Over time, Aristotle believed, people come to find genuine satisfaction and joy in living ethically.

Hedonic vs. Eudaimonic Happiness

Hedonic happiness focuses on pleasure, enjoyment, and positive feelings in the moment—such as savoring good food or laughing with friends. While these experiences are important, they are often short-lived and can lead to the hedonic treadmill, where people adapt and require more stimulation for the same level of happiness.

Eudaimonic happiness, by contrast, is rooted in meaning, purpose, and personal growth. It comes from living in alignment with values and contributing to something beyond oneself. Together, these two forms of happiness suggest that lasting well-being arises from balancing pleasure with purpose.

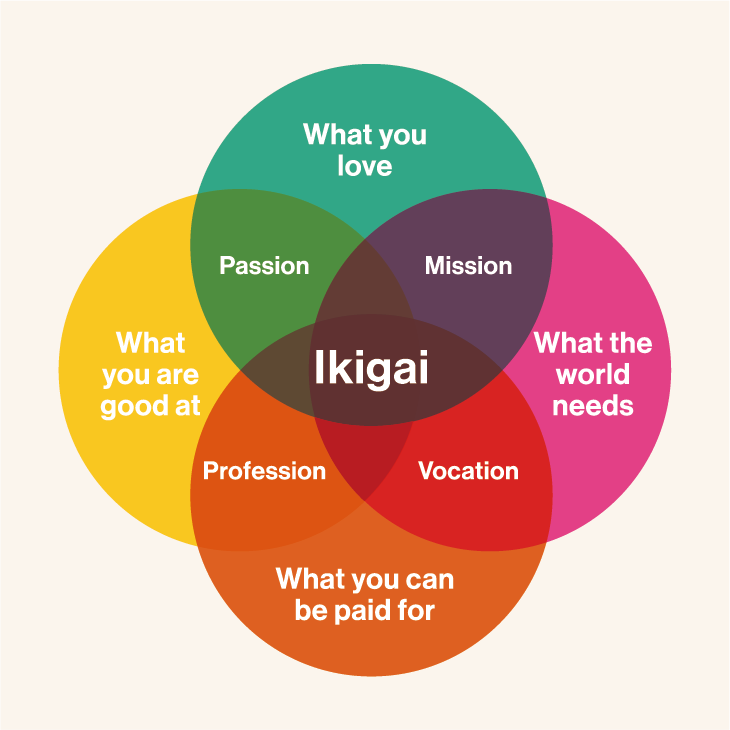

Ikigai (生き甲斐)

Ikigai is a Japanese concept meaning “a reason for being.” Derived from iki (life) and gai (value or worth), it represents purpose, passion, and what makes life feel worthwhile. Ikigai is often visualized as the intersection of what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what can sustain you. At its core, it points to finding fulfillment and joy in daily life, similar to the French idea of raison d’être.

Agape (ἀγάπη)

Agape is a Greek term describing selfless, unconditional, and sacrificial love. Often emphasized in Christian theology, it represents love as a conscious choice to seek the well-being of others, even in difficult circumstances. Unlike philia (friendship) or eros (romantic love), agape is benevolent and enduring—less a feeling and more a way of being that inspires goodwill and compassionate action.

The Shadow (Jungian Psychology)

The Shadow, a concept coined by psychologist Carl Jung, refers to the unconscious parts of our personality that we repress or reject. These may include instincts, fears, flaws, or socially unacceptable traits, but also forgotten strengths and creativity. Although hidden, the shadow influences behavior and often appears through projections onto others or in dreams. Jung believed that acknowledging and integrating the shadow is essential for personal growth and psychological wholeness.

Schema

Schema is a term from psychology and education (from the Greek schēma, meaning “form” or “shape”) referring to the inner mental framework through which we organize what we know, believe, and have experienced — a web of meaning shaped over time. Learning happens when new ideas connect to these existing schemas, sometimes reinforcing them and other times reshaping them. Because each person’s schema is formed through unique experiences, it influences not only how we learn, but how we interpret life itself; no two people understand or experience the world in exactly the same way.